What is shutter speed in photography?

It’s expressed as a fraction but what does it mean? Read on to be in the know

Shutter speed is pretty self-explanatory: it’s the speed at which the shutter inside your camera opens and closes, which affects how long light hits the camera’s sensor. As with ISO and aperture, your shutter speed changes the brightness of your photo.

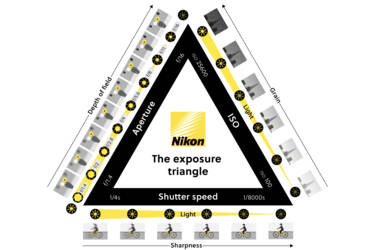

Shutter speed is one of three elements of exposure. The other two, ISO and aperture, are covered in separate articles. Together these three things make up what’s called the ‘exposure triangle’.

What’s in my kitbag?

Adjust the shutter speed using the command dials

Most cameras let you adjust shutter speed using one of the command dials. Newer mirrorless cameras such as my Nikon Z6II also let you choose shutter speed and other settings via the touchscreen on the back of the camera.

What shutter speed measurements mean

Shutter speed is expressed in seconds or fractions of a second, such as 1/200, and is a measure of how long the shutter stays open. So, the setting 1/200 means the shutter inside your camera will open for 1/200th of a second. The shutter speed you have set is also how long the light will hit your sensor.

The higher the number, the faster the shutter speed. So, 1/1000 is five times faster than 1/200. Higher settings, such as 1/1000, 1/2000 and above, are commonly used to freeze motion when photographing fast-moving subjects such as athletes or wildlife. High-end pro cameras like the Nikon Z8 can have max shutter speeds as high as 1/32000.

Conversely, lower numbers mean a slower shutter speed and the shutter stays open longer for light to hit the sensor. Because of that, slower speeds can produce creative blur effects like double exposures and light streaks. Using a slow shutter speed is sometimes referred to as ‘dragging shutter’ for this reason.

From left to right: 1/15, 1/125, 1/1000, 1/4000 seconds

How to use shutter speed creatively

Dynamic actions perfectly frozen, like someone mid-jump or a football player mid-catch, can pop if done correctly. Night scenes with streaked taillights can invoke a sense of mystery and nostalgia. Learning greater control of shutter speed will let you bring ideas like this to life.

Higher shutter speeds – think 1/1000th and faster – freeze motion. You can use that to perfectly capture a hummingbird mid-flight or a race car on the track. Photographing someone as they’re jumping can make it look as if they’re floating if you raise your shutter speed high enough to eliminate any motion blur.

Slower shutter settings, on the other hand, create blur. You can see the effect in the image below I took inside Grand Central Station in New York City. The building and objects are sharp, but the people are blurred. The effect was created by stabilising the camera on a flat surface and using a very low shutter speed.

Z6II + AFS NIKKOR 50mm f/1.4G + Mount Adapter FTZII. 50mm, 1 sec, f/5, ISO 100, ©John Bogna

The same principle applies to moving vehicles, water and anything else you want to smooth out or blur in your final image. By using specific lens filters called Neutral Density — or ND — filters, you can leave your shutter open long enough to blur motion even during bright sunlight, leaving the rest of the image untouched as long as your camera is stabilised.

Read more: The essential guide to filters: what to use for snow, water and effects

Shutter speed affects creative look. From left to right: ©Ben Moore, ©Scott Antcliffe, ©Pauline Ballet

How shutter speed affects exposure

Changing your shutter speed controls the brightness of your photo, either by letting more light in or cutting light out. Sometimes a slow shutter speed is the only option for getting the exposure you want. In astrophotography, for example, shutter speeds of 30 seconds to several minutes are common because the sensor needs much more time to gather light. However, longer than 30 seconds and the image will start showing star trails as the earth rotates, so you can either combine a series of shots or use a star tracker system which moves the camera slowly to stay in perfect line with the stars.

Whichever speed you use, you’ll have to counterbalance it against your other settings to get a good photo. If you’re in a dark room but still want minimal motion blur, you can lower your shutter speed to a certain point while boosting your ISO and using a wider aperture.

How to find and adjust shutter speed

Most cameras let you adjust shutter speed using one of the command dials. Newer mirrorless cameras such as my Nikon Z6II also let you choose shutter speed and other settings via the touchscreen on the back of the camera.

Shutter priority mode (the S on the camera mode dial) lets you control shutter speed while the camera automatically adjusts the other settings based on what you select. Using this mode is a good way to understand how shutter speed, ISO and aperture are all connected and allows you to home in on one setting to learn how it works.

Read more: Understanding camera modes

Choosing the right shutter speed

There is no correct shutter speed for every occasion, but you can use the principles we talked about here to determine what the best shutter speed is for your situation. If you need to freeze motion, use a fast shutter speed. If you need more light or want to create blur, use a slower one. Exactly what setting you use will require a bit of playing around.

Remember the drawbacks to each when choosing a shutter speed. Faster settings will cut down on light, so you must account for that by raising your ISO, opening your aperture, or both.

Play around with shutter speed until you achieve the desired result. From left to right, top to bottom: 1/15, 1/40, 1/125, 1/400, 1/1000, 1/4000 shutter speed.

Slower speeds will create motion blur, so make sure you’re using a tripod or keeping your setting above a certain speed when photographing hand-held. If your subject is stationary, for example, someone sitting for a portrait, 1/200th or higher should be enough to get rid of any motion blur. A hand-held photo might come out blurry from camera shake if your speed is too low, although newer cameras (and some lenses) with Vibration Reduction can compensate for that.

Try out different shutter speeds in different situations. Get a feel for how your camera works and, eventually, the adjustments become second nature. What’s important is getting out there to practice.

More in Camera 101s

Better photography starts here

Unlock greater creativity